“Dedicated to finding effective solutions for bird mite infestations of humans and their environment, encouraging those afflicted, facilitating research and a better understanding of human parasitosis.”

Bird Mite Characteristics

The term ‘bird mite’ will be used generically unless a specific species is named. There are also other types of nuisance mites which will bite humans and produce many similar skin problems. These include the rodent mite, straw itch mite, cheyletiella mite, et al; but this website does not specifically address these other species. Although some of the ‘strategies’ mentioned can be effective against them also.

Introduction

Bird mites (avian mites) are parasitic arthropods in the acari (tick/spider) family. There are reportedly 45,000 species of mites that are known. Only a few species of acaroid mites are parasites on mammals; but they can be very detrimental to the host, with symptoms ranging from mild discomfort to loss of health and even death. Research has shown that parasitic mites have evolved and adapted very well to a changing environment, and many are no longer host specific; and they have become problematic for many different mammals, including humans.

Of the two most common species, D.Gallinae is by far the more difficult to eradicate. It is smaller, can live much longer without a blood meal, and is more resistant to miticide chemicals than the NFM.

There are two main species of bird mites commonly found in North America. These are Demanyssus Gallinae (D. Gallinae) and Ornithonyssus Sylviarum (northern fowl mite or NFM). There are also other bird mite species found mainly in other regions of the world that are very similar, such as Ornithonyssus Bursa (tropical fowl mite). Most researchers contend that there could very well be other parasitic bird mite species still unclassified.

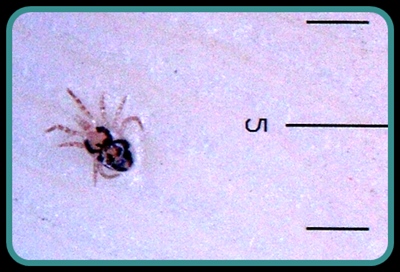

Image of mature NFM (O. Sylviarum), approximately .5 mm in length, X63 magnification. (photo courtesy Tokai J Exp Clin Med., Vol. 23, 1998)

The bird mite life cycle consists of: egg, larva, nymph, and mature adult. They can complete this cycle in about 7 days, depending on the environment. The mature mite has four pair of legs, and the immature nymph has three pair of legs. Bird mites have a sharp, protruding mouthpiece, which allows them to penetrate skin in order to obtain blood from the host mammal. The adult female needs blood in order to reproduce. The female mite typically is about 95% of the population. They are generally opaque/whitish but will be darker after a blood meal.

Although parasitic bird mites need a host mammal to survive and reproduce, research has shown they can survive for extended periods without a host. One Swedish study reported D. Gallinae can live nine months without a host. Several other studies confirm that they live at least eight months without feeding. NFM can live several weeks without a host.

“Red poultry mites (D. Gallinae) are a direct threat to economically valuable birds, suspected of passing on diseases like Newcastle Disease. But they have also been shown to be part of a wider chain transmitting diseases to people and other animals such as the food poisoning bacteria Salmonella, and equine encephalitis in horses.” Society for General Microbiology, September 9, 2007, “Bacteria Inside Red Mites Could Be Targeted To Control Poultry Pests”.

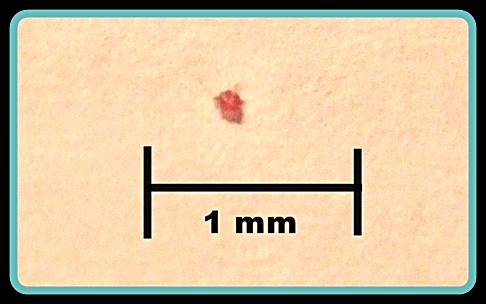

Bird mites are very small; a mature NFM is no more than about .5 mm in length, and D. Gallinae is typically no more than about .4 mm in length. A mature bird mite would be about the size of the period at the end of this sentence. Fully a third of this length comprises the front legs and mouthpiece, and so the actual body size is smaller than the total length. An unfed mature mite may or may not be seen with the naked eye. The NFM tends tend be slightly darker and more easy to see than D. Gallinae. The immature nymph is much smaller than an adult mite and will not usually be seen except with strong magnification.

Image of a mature blood engorged D. Gallinae (Demanyssus Gallinae), approximately .4 mm in length, 100x magnification. (Image courtesy Veterinary Dermatology 2008 Feb; Vol. 19)

The NFM tends to spend most of it’s life cycle on or near the host. A population can grow into the thousands very quickly. NFM is not only found on wild birds, but has been known to infest rodents, such as the Norway rat, common field mouse, and even pet gerbils; which means they can easily gain access to the home environment without a host bird ever being present. Both species of bird mites have been documented as being problematic for domesticated pets as well as humans.

D. Gallinae has been called a ‘chicken mite’, or ‘red mite of chicken’, as they were first identified on chickens. Normally opaque until feeding, they then become crimson red. They are most active at night and will hide during the day away from the host. They can so badly infest a chicken coop that some of the young may not survive. Chickens infested with bird mites have been shown to produce poorer quality eggs and fewer chicks. Farmers may have to resort to burning badly infested coops when the mite population cannot be controlled. This species, along with the NFM, are also known to infest sparrows, pigeons, starlings, and other varieties of wild birds and rodents in North America.

Magnified image of a mature bird mite indigenous to South America, approximately .7 mm in length. This mite was obtained from a home infestation in Brazil. (photo courtesy of Dr. Wambier, Dermatologist, 2008)

Environmental Characteristics

Bird mites normally hide or burrow during the day and are more active at night, corresponding to their inherent behavior to parasitize nesting birds. Humans bothered by bird mites will notice significantly more activity at night than in the daytime. In the home, bedding material and furniture are an ideal breeding ground for mites that will bite during the night and hide and reproduce deep inside when not active. Mites prefer cottons and fabrics as this can act like an insulating material where eggs can be protected from the environment.

A bird mite infestation in the home is often initially thought of as a flea infestation. People with pets will assume that if the parasite is this small it must be fleas. Bird mites are even smaller and do not hop the way fleas can.

Not Fleas!!!

Bird mites are able to find an appropriate host by means of their special receptors for moisture, heat and carbon dioxide (CO2). This is why people often notice them crawling near their mouth, nose, ears, eyes and groin area; especially at night. It is well documented that bird mites will parasitize the respiratory system, as well as skin and feathers of host birds. Mite thermal receptors are so sensitive that they can detect a difference of only 1 degree F in the environment. The female mite is typically 95% of the population, and they secrete a pheromone to communicate with others, which is why they can so quickly swarm the host mammal. And this can explain why they often bite in large numbers and can so quickly multiply once they have a host.

One other type of mite may be seen in pet and aviary birds. This is called the red mite (Dermanyssus). This nasty mite bites birds and sucks their blood. Red mites may be found on any species of bird…I have seen these mites infest an entire New York City apartment! Unfortunately, red mites aren’t very fussy about who or what they take their blood meal from! They can bite and feed on human blood, as well as the blood of household pets. During the day, mites can get into furniture, carpeting and woodwork, where they lay their eggs. Clean-up requires removal of the mites from the environment as well as from the birds. © 2006 Margaret A. Wissman, D.V.M., D.A.B.V.P., ExoticPetVet.net

Parasitic mites have evolved a very efficient systems for detecting a host mammal. As mentioned earlier, they have `chemoreceptors’ which allow them to detect CO2 and other scents from the host mammal, as well as pheromones which allows them to communicate with each other for swarming, mating, etc. The also have `mechanoreceptors’ which allows them to detect movement and vibration from the host mammal. And they also have `thermoreceptors’ for detecting warmth/heat and a change of temperature in the environment when a host mammal is present.

Magnified image of a mature bird mite, possibly O. Bursa. Photo submitted by one of our readers.

The mature adult is surprisingly quick, mainly due to the large front legs. The immature nymph moves slower due to its smaller size and one less pair of legs. It is likely that the slow crawling that is often felt on the skin of humans is due to the immature mite. Bird mite activity tends to be inversely related to the host mammals; if the host is active then mites are usually less aggressive, conversely when the host is sedentary, mite activity tends to increase.Humans and pets bothered by mites will notice significantly more mite activity while resting. (A ceiling fan or an oscillating fan can be used to try and keep mite activity to a minimum in a room.)

“Multiple reddened lesions on a human leg attributed to a home infestation of bird mites, later identified as D. Gallinae. These mites tend to swarm and often bite in large numbers. Photo submitted by one of our readers.

Bird mites are very hearty and adaptable to most any environment. Their fluctuating metabolism allows them to survive in cold weather and live for extended periods when no host is available. Entomologists call this ‘diapause’. They simply shut down their metabolism until the temperature is more appropriate. D. Gallinae can survive in temperature extremes of below freezing, to over 125 degrees F. (One study reports they survive to -4 degrees F.) There is also a fairly wide temperature and humidity range when mites will be active to parasitize and reproduce, and it is often dictated by how long it has been since they have fed. They are tenacious, and once they have identified a host, they are able to quickly adapt and remain in that environment indefinitely. Left unchecked, their population can soon grow into the thousands!

Bird mites are body-breathers and take in oxygen through pores in their exoskeletan. Some people have had success with killing mites on the skin by suffocating them using some type of thick product, such as petroleum jelly.

Avian mites have demonstrated a highly flexible DNA, which allows them to quickly adapt to unfavorable conditions with each new generation. There are documented cases of certain insecticides no longer being effective in eradicating them as they once did. Research has shown that some bird mites have the ability to revert to an earlier stage to avoid being rejected by the host’s immune system. A recent Michigan State University ‘Pest Management Manual’ states that several specifies of mite ‘ectoparasites’ are shown to have evolved into ‘endoparasites’ in the host mammals…making detection and eradication even more difficult.

Close up photo of a blood-engorged bird mite, most likely D. Gallinae. Normally opaque and very small; they are very difficult to see until after a blood meal. On a light background they often look like grains of red pepper.

Bird mite activity tends to increase in a warm and humid environment. Mites are most productive when the relative humidity is between 70%-90%. People that live in humid climates, such as Florida and California, report many more problems from bird mite infestation than those in arid climates, such as Arizona. If high humidity is an issue, then air-conditioning and dehumidifiers should be considered to reduce mite activity.

The intense itching and irritation is due to the saliva mites secrete when attached to the skin, and it may last for days after the mite is no longer attached; even when the skin does not show any visible signs.

Bird mites are known vectors of various pathogens in birds, livestock and humans. They can transmit disease causing organisms to the host, such as the virus of St Louis Encephalitis. The reports of human disease attributed to bird mites are rare, but they do occur. There have been reports by some people of strange fibers on the skin and Morgellons symptoms that started after a mite infestation, but the link is vague and requires further research. Some with a long term mite infestation will test positive for Lyme disease. It is hoped that at some point the CDC or NIH would take a closer look at human parasitosis and acariasis attributed to mite infestation.

Bird mite infestation of humans occur throughout the world, from Australia to England and throughout the USA. The species of mite may vary, but the symptoms are generally the same. Mites are no respecter of persons; whether young or old, male or female, vegetarian or carnivorous, and if in good health or not. Although, it is important to maintain a healthy immune system, as research has shown that mite populations tend to be higher in mammals with poorer health.

Mature bird mite image obtained by clear tape from the individual’s skin, and then examined under a microscope, where the digital image was captured. Image submitted by one of our readers.

Recommended Treatment Provider

We recommend you use a licensed professional to address a bird mite problem. Don’t wait or the problem will get much worse and more expensive to treat. We have a list of pest control companies that are specifically qualified to treat bird mites.

- They come to your house for no charge and give a free estimate.

- Even if you decide not to use them, you get free professional advice.

- Most pest control companies have never dealt with bird mites before. You need to use a bird mite specialist.

Follow this link to find a Qualified Local Exterminator near you.

Keep in mind that if bird mites are not treated correctly, even if the correct chemicals are used, they can become resistant to those chemicals. Don’t use a pest control company unless they have extensive experience treating bird mites.

Also, many of our readers have followed up with (or used outright) natural solutions and pesticide-free, such as on our Treatments Protocols page Follow this link to that page.

Natural and DIY Solutions

In addition to local exterminators, we offer a list of other natural, non-pesticide and/or do-it-yourself products that we have found helpful on our Treatments Protocol page. Follow this link to the Treatments Protocols page.

Both D. Gallinae and NFM are documented in numerous research journals as being a nuisance pest on many species of birds, wildlife, domesticated animals and even humans. It is quite clear that bird mites are not host specific, and they have adapted very well to a changing environment (as mites tend to do).